Researchers at Brigham Young University have published a paper detailing the development of an ultrasoft silicone with a functional stiffness gradient, and they have done so while researching how to print vocal cords.

Why would anyone need to 3D print a vocal cord in the first place?

Read on to know more.

Vocal Folds

Vocal cords, also known as vocal folds, are the two thin bands of smooth muscle tissue located in the larynx at the top of the trachea. These folds are responsible for producing sound such as speech or singing when they vibrate as air (your breath) passes through them. The pitch of the sound produced by the vocal folds is determined by the tension and thickness of the folds, as well as the rate at which they vibrate, much like a stringed instrument.

Researchers in the field of phonetics use synthetic models of the vocal folds to see how factors such as the frequency of vibration and the minimum lung pressure needed to initiate vibration affect human voice production.

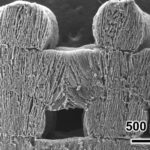

These models are often made with layers of silicone of different stiffness to mimic the structure of human vocal folds, which are composed of various types of tissue.

One common method for creating synthetic models involves casting layers one after another. This method can produce models that have vibratory characteristics similar to human vocal folds. However, models produced with this method tend to have a high rate of failure, a relatively long fabrication time, and results in models with distinct layers. The layers in a real vocal cord are less distinct and more gradual.

Therefore, accurate and reliable models need to be robust, and have spatial variations in stiffness. And that’s why this research into AM-produced vocal cords has been conducted.

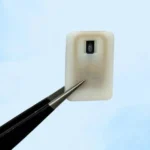

The image above shows the results of the vocal fold printing experiment.

Printing of Vocal Folds

In the research by Brigham Young research, a custom printing technique was developed to create silicone parts with varying levels of stiffness.

First up, the design for each vocal fold section was modeled in CAD before being sent to a custom slicing software. The material properties for each section were assigned a specific stiffness value within the slicer. The slicer then used this information to determine the optimal ratio of materials from extruders A and B needed to achieve the desired stiffness for each section.

Based on this calculation, the slicer generated g-code instructions to control the 3D printer and print the sections with the desired stiffness.

The printing was achieved by using two separate extruders, designated “A” and “B”, to deposit UV-cure silicone into a special support matrix made of a gel-like silicone oil.

Both of the extruders were filled with uncured silicone that would each solidify to different stiffness levels.

By adjusting the extrusion rates of the two extruders, the printed parts were able to have a range of cured stiffnesses that ranged between those of the “A” and “B” materials when the ratios were changed.

Once the printing was complete, the parts were cured, removed from the support matrix, and cleaned for further analysis.

Conclusion

The printed silicone samples had a tensile elastic modulus range of 1.11 kPa to 27.1 kPa, which was classed as ultrasoft at the lower end, and therefore suitable for synthetic vocal fold modeling.

Additional cuboid test specimens were printed with these methods, to test that the researchers’ finite element simulations were robust in terms of stiffness variation, and were deemed to be agreeable.

So overall, mission accomplished. Printed vocal cords are a reasonable substitute for single material models, and traditionally casted models. However, regarding the desired mechanical reliability of the specimens, the researchers noted that the viability of the printed models was not yet equal to that of the cast models. This was attributed to the fact that this printing method is new, and vocal fold models with lower failure rates will be produced as the technology matures.

You can read the full paper titled “Three-Dimensional Printing of Ultrasoft Silicone with a Functional Stiffness Gradient” at this link.