A student at New Zealand’s Waikato University is looking to cancerous cells to further research into potential cures. Masters student Shalini Guleria plans to grow the cells outside of a patient’s body for various tests with aim of reducing the need for and dangers of long-term processes like chemotherapy.

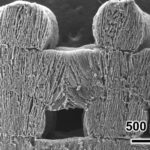

While the biopinting itself is incomplete, Guleria has begun printing plastic models as the basis of the eventual cells. The actual bioprinted versions will use the plastic from the prototype models with MCF-7 cancer cells, hydrogels and various binding materials, which will eventually grow into a life-sized tumor.

“In the future what could happen is, if someone has breast cancer, we could take their tumor cells and print out a tumor and try out different drugs on it and see which treatments work and what works best for the patient“, explained Guleria. “It’s all about making treatment more patient-specific.”

While she was always interested in tissue research, the death of a friend at the hand of Lukemia really hit home and hardened her resolve in fighting cancer. “She was only 17 and passed away a year after her diagnosis“, said Guleria. Now, she has dedicated all her work to preventing the damage done by various types of cancers.

Growing Cancerous Cells For Research

Current research is ordinarily conducted on 2D models and petri dishes. The aim of this bioprinting project is to add that extra dimension and work with a more informative system. Since these will be more 3-dimensional, they can provide a better readout of the human body as it is. It also allows for a better means of measuring the growth of tissues and fibres that connect the cell organelles.

Aside from studying the cells themselves, the research can measure the precise effects of the Cisplatin and other chemotherapy drugs, providing a far better understanding of how they operate on a micro-level. Therefore, it could be key in regulating dosages and amping up the safety of using such treatments. Guleria wishes to go even further by creating a model for individual treatment. The research could then potentially create personal regimes, far more suitable for each patient’s body.

“We may be able to take the cells from someone who has cancer, and use them to produce something we can test very specifically for that patient,” added Guleria.

Cancer research is particularly tricky. There’s never a one-size fits all solution for cancers because cancers aren’t one disease. The entire field of cancer research encompasses so many varying strains that confound researchers to this day. Luckily, a means of studying the tumor cells themselves can aid efforts immeasurably. It will inevitably lead to new processes and medications that suit the patients on an individual basis.

Featured image courtesy of the University of Waikato.