Researchers from Oak Ridge National Laboratory have published a paper highlighting the effects of ash content in bioplastics, and have reached the conclusion that it doesn’t really do much at all.

This is good news…but why?

Read on to find out.

Ash

Biomass ash is the inorganic, incombustible mineral found in plant matter.

It appears in the form of spheres, and consists of elements such as calcium, iron, magnesium potassium, aluminum and manganese.

As we have seen in previous articles, plants containing natural polymers such as hemicellulose can be used as additives to PLA biocomposites, for bulking up the material as well as altering the mechanical properties.

The researchers at ORNL wanted to know to what extent the presence of these ash spheres affect the viability of bioplastic, biocomposite and also biofuel production. The aim was to determine how much ash is acceptable in biomass when producing such materials.

The biomass in question came from switchgrass and corn stover fibers, and they were added to PLA material, before being formed into dogbone specimens for testing.

“We went as high as 12% ash content on our corn stover biocomposite and found mechanical properties like stress and strain tolerance and tensile strength to be acceptable,” said Xianhui Zhao, a researcher at ORNL.

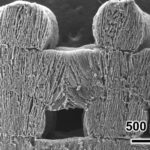

You can see a microscopic ash sphere in the image below.

It is important to determine the levels of ash content when processing into bioplastics and composites, because it has been shown to have a negative impact on biomass size reduction, flowability, reactivity, and feedstock quality.

In terms of processing, biomass ash is a cause of abrasive wear in biomass processing equipment.

Knowing what levels of ash are acceptable for feedstock production is therefore important in maintaining the quality of the feedstock, and in reducing the wear of processing equipment.

Ash in biomass falls into two categories, named physiological ash, and exogenous ash.

Physiological ash appears inside biomass as it grows and is a result of mineral uptake during growth stages.

On the other hand, exogenous ash comes from outside the plant, in the form of dirt and soil that can accumulate. The largest portion of exogenous ash comes from physical handling of biomass during harvesting.

Preparation

The switchgrass and corn stover fibers were air-dried to reduce moisture content, before first being ground with a hammer mill, and then with a knife mill. These two milling steps gradually reduced the particle size down to 4.76mm, and then 1.0mm respectively.

Each feedstock was then analyzed for ash content to determine the baseline ash content. A combination of size fractionation via sieving and fiber cleaning via ultrasonication was used to achieve a variation in the ash content levels for each feedstock.

The graphic in the table summarizes things quite nicely.

Sieving like this allowed the researchers to separate the exogenous ash from the natural fibers and allowed the transfer of detached ash material to lower screens, thereby resulting in a significant ash content gradient across the size fractions retained on each screen.

The ultrasonication process takes place in deionized water, and washes ash from the feedstock and collects it at the bottom of a vessel.

The purification process is mainly used to detach and remove external ash particles from the biomass to add variability of ash content to the samples.

When the biomass particles had been sorted into different ash fraction samples, the low-ash biomass was converted to biofuel, and the high-ash biomass was converted to biocomposite materials with PLA.

Conclusions

As mentioned previously, the researchers went as high as 12% ash content in their corn stover/PLA biocomposites without significant loss of tensile strength or without altering the stiffness too much.

This is a fairly high ash content, and means that there is potential to utilize high ash content biomass in the production of biocomposites.

Typically high ash content biomass products are sold as low value materials – because filtering and sorting the lower ash content materials is more expensive.

However, the research demonstrates that the high ash-biomass stream from biomass fractionation may be more valuable than once was thought, due to the negligible effects on the mechanical properties when used in additive manufacturing feedstock production.

Or in other words, using high ash content biomass could make biocomposites cheaper.

The paper, titled “Impact of biomass ash content on biocomposite properties” has been published in Composites Part C: Open Access, and it can be found at this link.