Surfaces vary in shape, color, texture, opacity and gloss. Most of these can be replicated by selecting the right material or by altering the geometry of the part printed (in terms of shape and texture). However, until now, modifying the glossiness of a 3D printed part has proven to be elusive.

Enter a team of researchers who have found a solution which can enable a new layer of realism to 3D prints.

The team was formed from researchers at MIT, University of Lugano, Max Planck Institute, and Princeton University.

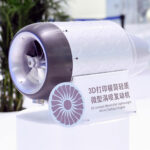

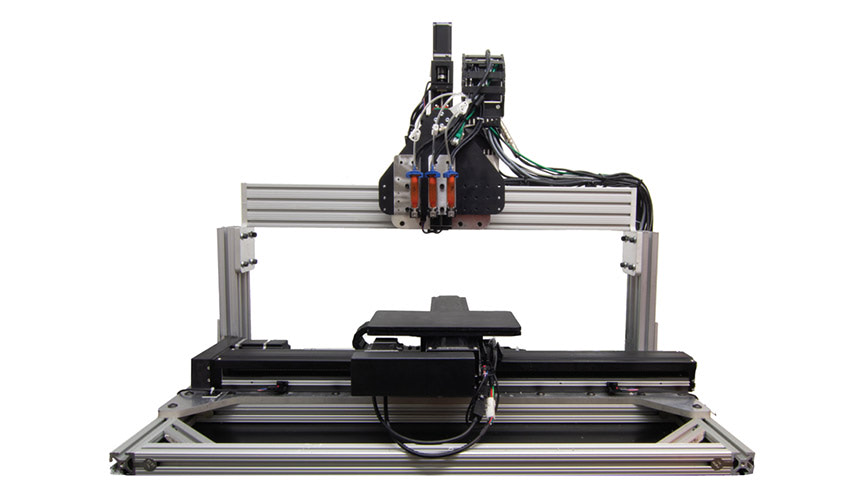

The printer operates as a normal filament deposition 3D printer but with the addition of a pressurised varnish reservoir. The varnish is applied to the printed surface by means of large nozzles which can deposit varnish droples at various sizes and speeds. The varying of these parameters allows control over the glossiness of the applied varnish.

The volume of varnish is metered via a needle valve, which can vary the size of the varnish drop based on the speed of the needle valve opening.

“The faster it goes, the more it spreads out once it impacts the surface,” said Michael Foshey, researcher at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL).

“So we essentially vary all these parameters to get the droplet size we want.”

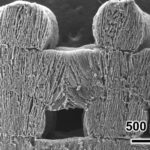

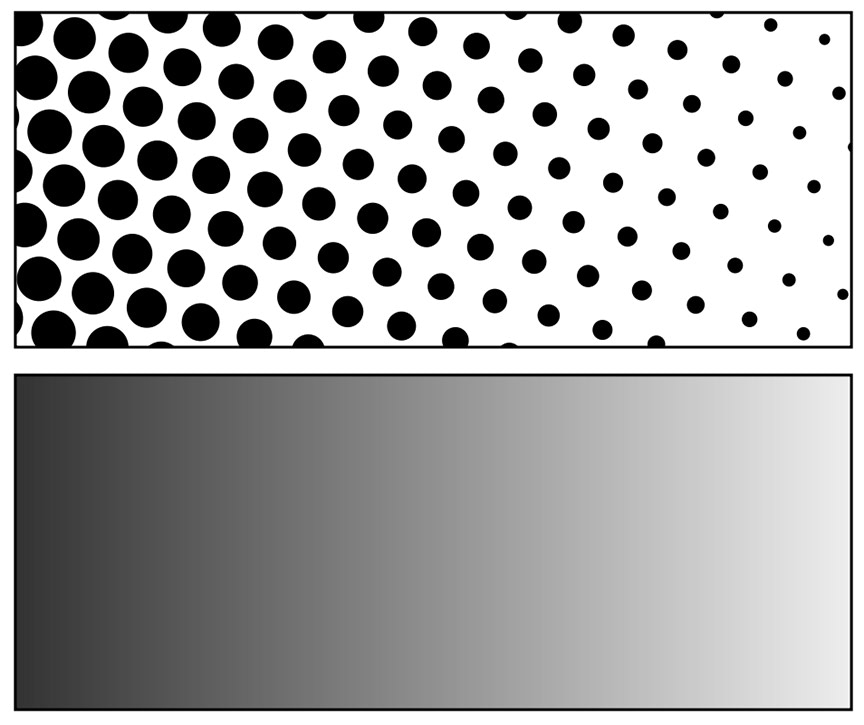

By varying the dot size the researchers are able to use the technique of halftoning to create a surface that looks continuous to the human eye, but on closer inspection is just dots spaced out, much as you would expect from holding a colour comic book up to your face. At close distance, all you see are dots. As you move the book further from your eyes, the dots create the illusion of different tones, even though they consist of just a few colors.

The same goes for this printer system. The “inks” consist of just 3 off-the-shelf varnishes, which are gloss, matte and a glossy/matte. By varying the distribution and size of these dots, a full spectrum of glossiness is achievable, just like the full gamut of colours is available from just 3 or 4 in a comic book.

“Our eyes actually do the mixing itself,” said Foshey.

The team sees future applications where the technology could be used to reproduce fine art pieces so that the copies could be sent out to museums and galleries for folks to enjoy without risking the original piece.

Additionally, the new developments could prove useful to the prosthetics industry, where the aesthetics of an artificial limb could be improved to look more realistic as opposed to the “flat” appearances of current prosthetic devices.