Mosquitos suck. That’s not an insult, it’s just what they do. And they do it all over the world except for Antarctica and a few other subpolar island locations (such as Iceland).

They are vectors for such diseases such as malaria and dengue, and are responsible for one million deaths per year, according to the WHO. They are literally the world’s deadliest animal. And if they’re not killing us in huge numbers, their bites are incredibly annoying, causing irritation, swelling, rashes, and sleepless nights for many.

There are many solutions for repelling these hellish insects, but they are far from perfect.

Wearable Repellent

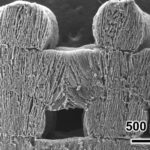

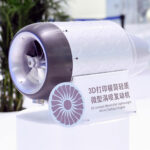

A team of researchers from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) in Germany have developed a potential solution that may prove to be a step in the right direction, and their answer comes in the form of a 3D printed wearable containing a skin-friendly chemical repellant. You can see a printed ring-like version of the wearable in the image below.

The most effective insect repellents tend to be synthetic in nature, with the chemical “DEET” being highly popular. Some of these chemicals can have side effects, and most of them are not fun if you accidentally get them in your eyes or mouth. Certain products have been found to be fairly toxic when ingested, and there have even been reports of seizures and even deaths associated with DEET usage (although those numbers are very small in comparison to usage).

Natural repellents are available, but they tend to wear off very quickly, requiring multiple applications.

The 3D printed wearable solution tries to find the middle ground by creating a product that is both long lasting, effective, and safe to use. To that end, the researchers opted to make their prototypes using a chemical named “IR3535“, which is an insect repellent developed by MERCK.

The chemical is encapsulated into the biodegradable, 3D printable feedstock (PLA) and is then printed into the form of the wearable, be it a ring, a bracelet, or whatever the designer chooses.

A maximum loading of 25% of the repellant (by mass) was achieved in the process, and the repellent-release rate was shown to increase with temperature. At ambient temperatures the release-time constant was shown to be in the order of 10 days.

“The basic idea is that the insect repellent continuously evaporates and forms a barrier for insects,” said Fanfan Du, lead author of the study, and PhD candidate at the MLU.

Kinder to Your Skin

Mosquito sprays containing IR3535 have been shown to be less of a skin irritant than DEET and have been used for years, according to the researchers. The maturity of the product combined with the lack of irritation made the chemical an ideal candidate for the experiments.

“The basic idea is that the insect repellent continuously evaporates and forms a barrier for insects,” explains the lead author of the study, Fanfan Du, a doctoral candidate at the MLU.

The rate at which the insect repellent evaporates depends on many different factors, including temperature, concentration and the structure of the polymer used.

While the prototypes have been effective in a controlled environment, further research needs to be carried out to determine how well the rings function under actual conditions.

Both DEET and IR3535 are effective against multiple insect types.

The team has published their findings in the International Journal of Pharmaceutics, and you can read that over at this link.