Researchers from MIT have figured out a means of heat treating 3D printed metals so that they can be used in high temperature, high stress environments.

This means that one day it could be possible to 3D print superalloy turbine blades with similar mechanical properties and reliability as conventionally manufactured blades.

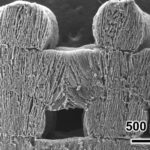

Microstructure

Traditionally, turbine blades and stator vanes are cast, and the molten metal is allowed to solidify in a lengthwise manner along the mold, resulting in larger, more robust grains that form in the direction of most stress.

It is preferable to use additive manufacturing for turbine blades for a variety of reasons including cost and environmental benefits. But until now, the printing process has resulted in parts that are susceptible to creep, which is exactly what you don’t want in a hot spinning metal part that requires mere microns of clearance at the end.

Turbine blades are very precise, and creep can result in the blade stretching and deforming under loads and heat. This creep is a result of the printed microstructure which can result in very fine grains measuring in the region of tens to hundreds of microns in length. In order to reduce the creep from such small grains, the grains must be produced.

By heat treating printed metal parts with induction heating, the MIT researcher found that they were able to quickly melt and reform the grains into larger columnar grains aligned with the axis of greatest stress, which are more resistant to creep.

This extra heat treatment stage means that it is possible, in principle, to produce 3D printed superalloy turbine blades that retain their strength and dimensional stability to the point that they can function in the extreme environment of a gas turbine engine. Of course, the extra design freedom allowed by 3D printing means that new turbines and stator vanes with new geometries can be produced, which can potentially improve fuel consumption and energy efficiency.

“In the near future, we envision gas turbine manufacturers will print their blades and vanes at large-scale additive manufacturing plants, then post-process them using our heat treatment,” said Zachary Cordero, Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT.

“3D-printing will enable new cooling architectures that can improve the thermal efficiency of a turbine, so that it produces the same amount of power while burning less fuel and ultimately emits less carbon dioxide.”

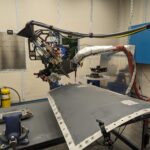

Induction Heating

By passing the printed metal through an induction coil at a particular speed, the researchers found that it resulted in the directional recrystallization of the small grains.

This method of heat treatment is almost a century old and has been used on wrought metals and alloys in the past.

By passing the nickel-superalloy parts at a speed of 2.5 millimeters per hour at a temperature of 1,235 C the team found they were able to maintain a thermal gradient in the part resulting in the melting of the fine grains and recrystallization in the direction of stress. After the part moves through the heated coil, it is passed directly into a bath of room temperature water for rapid cooling.

“The material starts as small grains with defects called ‘dislocations’, that are like a mangled spaghetti,” said Cordero. “When you heat this material up, those defects can annihilate and reconfigure, and the grains are able to grow. We’re continuously elongating the grains by consuming the defective material and smaller grains — a process termed recrystallization.”

The appearance of the columnar grains was confirmed by electron microscopy.

The next step is to move away from the rod-shaped metal pieces used in the experiments and move towards more turbine-blade shaped parts.

The research has been published in a paper titled “Directional recrystallization of an additively manufactured Ni-base superalloy” in the Additive Manufacturing journal.

You can access that paper over at this link.