We’ve previously covered the efforts of Washington University in 3D printing wireless communicating objects. The university created a range of objects that could communicate with other objects without electricity, conveying basic information using antennae. Now, researchers are applying the same principle to track object usage. These new wireless self-track objects use two antennae to convey relatively complex information.

“We’re interested in making accessible assistive technology with 3D printing, but we have no easy way to know how people are using it,” said co-author Jennifer Mankoff, a professor in the UW’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering. “Could we come up with a circuitless solution that could be printed on consumer-grade, off-the-shelf printers and allow the device itself to collect information? That’s what we showed was possible in this paper.”

One of the devices the team is developing is a medicine container bottle that can relay its usage times and info. The team previously created objects like containers that could inform the user when it is running low. While the old devices could only relay basic info, these new ones make use of the two antennae to relay more complex stuff into the wi-fi signals. Take for example the medicine bottle: it has an antenna to detect when it opens and another to detect when it closes. This allows the researchers to gather data about usage times, recording both instances.

Backscatter & Information Relay

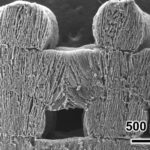

“The gear’s teeth have a specific sequencing that encodes a message. It’s like Morse code,” said co-author Justin Chan, a doctoral student in the Allen School. “So when you turn the cap in one direction, you see the message going forward. But when you turn the cap in the other direction, you get a reverse message.”

Similarly, the researchers are working on an insulin pen that could monitor its usage and signal when it’s running low. Since people may use their insulin pens outside of wi-fi range, they needed a comprehensive solution. They decided on altering the physical design of the gears to store the data physically using those gears. It stores that information by rolling up a spring inside a ratchet that can only move in one direction.

According to the researchers:

Each time someone pushes the button, the spring gets tighter. It can’t unwind until the user releases the ratchet, hopefully when in range of the backscatter sensor. Then, as the spring unwinds, it moves a gear that triggers a switch to contact an antenna repeatedly as the gear turns. Each contact is counted to determine how many times the user pressed the button.

The researchers will present their findings on Oct. 15 at the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology in Berlin. These sorts of applications are unique to 3D printing and advance the uses of the technology. The research is coming along in new ways and developing more complexity.

Featured image and video courtesy of Washington University.